The senate

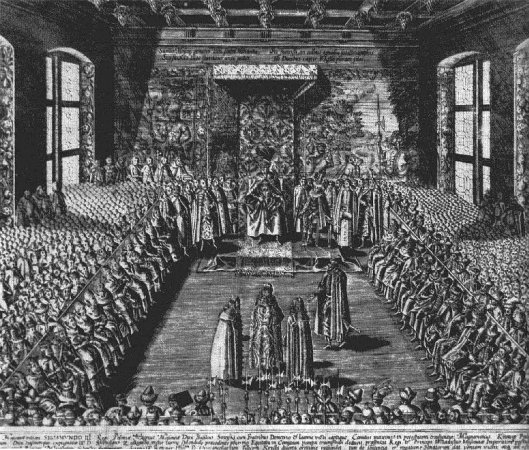

The senate was established in 15th century, during forming of the Chamber of Deputies in the sejm as the representation of the nobles. In fact, senate was a transformed royal council, which constituted of high officials, appointed by the king. The organisation of the senate began to stabilize itself in the beginning of the 16th century. The make-up of the senate was established and closed by the king Sigismund I the Old. It constituted of archbishops, bishops, voivodes, castellans, konarski castellans [who derived from “koniuszy” office - Masters of the Horse of the Kujawy area] and ministers: Grand Marshal of the Crown, Court Marshal, Grand Chancellor, Deputy Chancellor and the Grand Treasurer of the Crown. The members of the senate were definitely dignitaries. The Court Treasurer and the Hetmans were not included into the senate, as these offices became more stable in the beginning of the 16th century, that is after the composition of the senate was defined. The senators amounted to 87 individuals in the beginning of the 16th century, 94 after incorporating Masovia (1526) and after signing the union with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania - 140. King Sigismund I also determined the order of participation in the senate but it was changed in 1569 after the dignitaries of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Royal Prussia were included in the senate. This order was in power until 1768. According to the order, the first senator was the archbishop of Gniezno. He was followed by the archbishop of Lviv and the bishop of Cracow. The first of the secular senators was the castellan of Cracow, then the voivodes followed, then castellans of Vilnius and Grodzieńsk, starost [“starostwo” was a Polish term for eldership office] of Samogitia, ministers and other castellans. The senators took a senator’s oath, in which they obliged to advice the king faithfully.

The position of the senate derived mainly from the custom. The sejm legislation, in form of regulatory standards regarding this chamber, which can be found in resolutions, determined the senate basically as an administrative, government body. According to these standards, shaped in the previous period, the essential competence of the senate members was taking part in deciding on key state matters, in particular the state defence, wars and foreign policy. Their task was also, if necessary, giving consent to legislation, what in fact gave the senators the legislative initiative, via consultations (so called deliberatoria). The competences of the senate in scope of state finances included controlling securities, endowments and settlements of royal demesnes - in general expressing opinion on alienation of possessions and goods of the royal demesnes, differentiating them and controlling the treasury accounts. The senate had also the voting power in economic matters, coinage and adopting tariffs. The participation of the senators in the administration of the law was combined with performing executive duties. The senators were also obliged to take part in sejmiks. The Nihil novi constitution of 1505 granted the senate the right to cooperate with the Chamber of Deputies to create resolutions.

The provenience of the senate was sanctioned with a custom, as the body acting at king’s instigation and at his side but on the other hand the senate was also the third sejming estate, what was - like the whole sejm - constituted in Henrician Articles (1573) as the permanent, constitutional body of fixed political position, which was obliged to secure and control the king’s decision making process in matters determined in the constitution. From among the senators, according to Henrician Articles (1573), the council of resident-senators was elected. It was a permanent body, serving the king with advice and wisdom, what also determined a legal strengthening of fixed advisory function of the royal council.

The king called the senators to the sejm in the same time as the Chamber of Deputies. Senate gathered around the king after the service, in which the senators took part along with the king and the deputies. The essential elements of the controlling, advisory and consultative competences of the senate were wota [senators’ opinions]. They were a part of the sejm procedure. In substantial sense, they expressed senate’s opinion on king’s proposals. As a result, the senate was not bound by the unanimity rule, as the senators by turns spoke their minds [in Polish “wota”], which were evaluated by the king and summed up in a conclusion. Usually it was voiced by the chancellor, but it happened also that the monarch announced the conclusion himself. The demonstrated solidarity with the royal programmes was in practice very often apparent, superficial and with no greater value. The meaning of wota was in who spoke it but also in its content, manner of speaking, atmosphere and situation. They were in a way a measure of social tensions. As a matter of fact, the senators’ wota were an opinion poll of the royal court plans and have very little influence on the proceedings and the final resolutions of the sejm.

The senators played a major role as the ministers of the Commonwealth and the resident senators, relatively also the members of the various councils. The development of these functions started the process of gaining more importance by the senator boards, called by the king since the 17th century. At the turn of the 17th century there was a major crisis in the political role of the senate. It was widely and commonly criticised, what deepened under the rule of John III Sobieski and even grew stronger under the rule of Saxon kings. The difficult political situation caused the nobility to become even more distrustful when it came to senators’ actions regarding the state matters. Both in the eyes of the nobility and in the doctrine the senate was no longer considered an indispensable link (aequilibrium) between the majesty and the freedom, contrary to the previous mindset. This peculiar trust crisis to this public institution was a result of a bigger crisis, in which the Commonwealth found itself these days. This situation became the stimulus of the evolution of senate - its position, functioning as well as its mode of action.

See: S. Kutrzeba, Sejm Walny dawnej Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej [The General Sejm of the former Commonwealth], Warszawa 1921; J. Bardach, Początki sejmu, [The beginnings of the sejm] in: Historia sejmu polskiego [The history of Polish sejm], t. 1, Warszawa 1984, red. J. Michalski, s. 5-62. W. Uruszczak, Sejm walny w epoce Złotego Wieku [1493-1569] [The general sejm in the Golden Age] in: Społeczeństwo obywatelskie i jego reprezentacja [1493-1993] [Civil society and its representation (1493-1993)], red. J. Bardach, cooperation: W. Rudnik, Warszawa 1995, s. 48-61; W. Uruszczak, Sejm walny koronny w latach 1506-1540 [Crown Great Sejm in 1506 - 1540], Warszawa 1980. W. Uruszczak, Sejm w latach 1506-1540 [Sejm in period 1506-1540], in: Historia sejmu polskiego [The history of Polish sejm], t. 1, Warszawa 1984, red. J. Michalski, s. 63-113. A. Sucheni-Grabowska, Sejm w latach 1540-1587 [Sejm in 1540-1587 ], in: Historia sejmu polskiego [The history of Polish sejm], t. 1, Warszawa 1984, red. J. Michalski, s. 114-216; K. Grzybowski, Teoria reprezentacji w Polsce epoki Odrodzenia [Theory of representation in renaissance Poland], Warszawa 1959. W. Czapliński, Sejm w latach 1587-1696 [Sejm in period 1587-1696], in: Historia sejmu polskiego [The history of Polish sejm], t. 1, Warszawa 1984, red. J. Michalski, s. 217-299. E. Opaliński, Sejm srebrnego wieku 1587-1652. Między głosowaniem większościowym a liberum veto [Sejm of the Silver Age 1587-1652. Betwixt majority voting and liberum veto] , Warszawa 2001; I. Malec-Lewandowska, Sejm walny koronny Rzeczypospolitej i jego dorobek ustawodawczy [The Crown general sejm of the Commonwealth and its legislative achievements]. 1587-1632, Kraków 2009; H. Olszewski, Sejm Rzeczypospolitej epoki oligarchii (1652-1763). Prawo-praktyka-teoria-programy [Sejm of the Commonwealth in the oligarchy era (1652-1763). Law-practice-theory-programs], Poznań 1966;3, Poznań 1966). S. Ochmann-Staniszewska, Z. Staniszewski, Sejm Rzeczypospolitej za panowania Jana Kazimierza Wazy. Prawo-doktryna-praktyka, [Sejms of the Commonwealth under the rule of John II Casimir Vasa. Law-doctrine-practice] T. 1, Wrocław 2000, s. 276-291. J. Michalski, Sejm w czasach saskich, [Sejm under the rule of Wetting dynasty] in: Historia sejmu polskiego [The history of Polish sejm], t. 1, Warszawa 1984, red. J. Michalski, s. 300-349.