The Chamber of Deputies

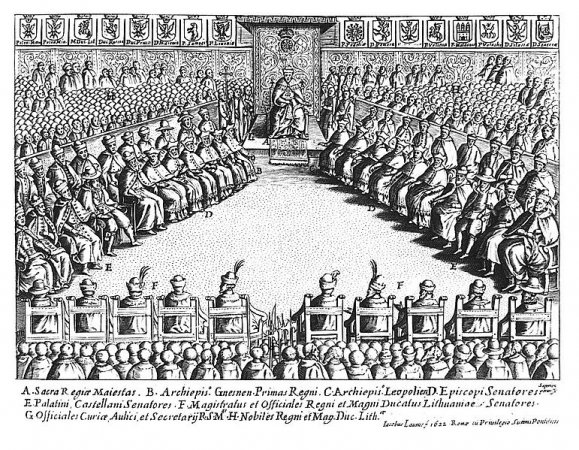

The Chamber of Deputies was a part of the former Polish Sejm, being an embodiment of one of the sejming estates. The origin of its isolation as a separate part of the sejm may be found in the sejms convened by the king Casimir IV Jagiellon. The earliest accounts of creating a separate chamber date to year 1468, when the king Casimir IV Jagiellon ordered the provincial sejmiks (of Greater Poland in Koło and of Lesser Poland in Wiślica) to appoint two deputies each and later all the county sejmiks in the Kingdom, who were to gather in Piotrków to take part in general sejm, what happened on 9 October 1468. In such a way the practice of creating the sejm with deputies chosen in sejmiks, who constituted a separate chamber - and not by inviting only the delegation of the general sejmiks or by a direct, personal participation of the noblemen - became established in the next sejms convened by the king Casimir IV, which took place almost every year, becoming a permanent rule of organising the sejm. Performing a duty of a general sejm deputy chosen during a sejmik was a proof of popularisation of the representation rule, which prevailed the rule of direct participation of all the entitled to vote. The presence of the deputies became an essential part of the general sejm. In the first half of the 16th century the representation of the nobility in the sejm, forming the Chamber of Deputies, constituted of deputations of voivodeships and counties, chosen during sejmiks. The deputation of a specific area did not represent the whole nobility estate but a community of the local nobility, called communitas terrae. It was quite common these days that every province chose its own deputation. However, in sejms convened in the ‘30s of the 16th century this distinction disappeared. The Chamber of Deputies developed into a one, common organism and was a composite of deputations of separate voivodships and counties but they were acting uniformly. In first in the first half of the 16th century it was customary for the senators to choose half of the deputies in the deputation of the voivodship or county, the rest was appointed by the nobility. This custom was abolished in 1537, however later on it was not unusual that the nobility in sejmiks chose magnates as their deputies. The amount of the deputies was inconstant and dependent on old customs. Trying to put things in order, king Sigismund II Augustus tried to limit the number of deputies, amounting on average to 93 individuals, issuing an ordination in 1552, in which, taking into consideration old customs, he set the number of the sejm deputies to 59. Leaving bigger deputations in Cracow, Poznań, Sandomierz and Kalisz voivodships (6 deputies each), the king decreased deputations of other voivodships (on average to 2 individuals), except for Masovian (7), Ruthenian (5) and Sieradz with Land of Wieluń (4). The king’s proposal of electoral law was subject to criticism. In fact, it resulted in no greater change in the number of deputies. The change came with signing the union with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (1569) and creation of the common sejm of the Commonwealth, which the Lithuanian deputies were also obliged to attend. Their number amounted to 44 - 2 deputies from every sejmik plus 2 deputies from Vilnius city. However, as a consequence of incorporating the Podlachia, Volhynia, Bratslav and Kiev voivodships, the Chamber of Deputies gained 20 more deputies, who came from these voivodships. The same happened after incorporating the Royal Prussia to the Crown, 10 more deputies were added to the Chamber of Deputies. In such a way, after 1569, 93 deputies came from the old Polish Kingdom, 20 from Podlachia, Volhynia and Ukraine, 10 from Royal Prussia and 44 from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, so altogether 167 deputies from all the lands of the Commonwealth. In this connection, it happened that the number of chosen deputies was higher, especially if the pre-sejm sejmik was split into two parties (called division or split), each choosing own deputies... so two sets of deputies appeared at the sejm. In the case of questioning the choice of individual deputies, the sejm carried out rugi, that is checking legal validity of their deputy mandates. It was done by the chamber, which has the power to acknowledge the validity or not. The deputies who were denied the right to represent their sejmik in this sejm were removed [in Polish “rugowani” - evicted, that’s where the noun “rugi” comes from]. The same rule applied to denying the right of being the deputy and removing the individuals who performed other functions, like, for example, deputies of the Tribunal, relatively also to those who had no rights at all, like expellees or outlaws. The order of the deputy seats in the Chamber of Deputies was established in the union act in 1569, similar to the royal council (senate) order, introducing the system of “interweaving” the old Crown deputies with the ones newly included into the sejm. The deputies were elected during the pre-sejm sejmiks, during which also the “deputy’s instructions” were prepared. Staying at the sejm was inevitably connected with major expenses. Usually that’s why the deputies were given daily allowances, at first paid by the state treasury but in the beginning of 17th century this duty was shifted to the voivodship treasury. The proceedings of the Chamber of Deputies were managed by the marshal of the Chamber of Deputies, who was elected during the first day of the sejm, right after the first religious service. The election of the marshal of the new Chamber of Deputies was managed by the previous owner of the speaker’s staff [referred as to “marshal of the old staff”] or the oldest deputy present. There was a rule of “alternata”, so the marshals were elected by turns from the deputies of the Greater and Lesser Poland, later on also from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

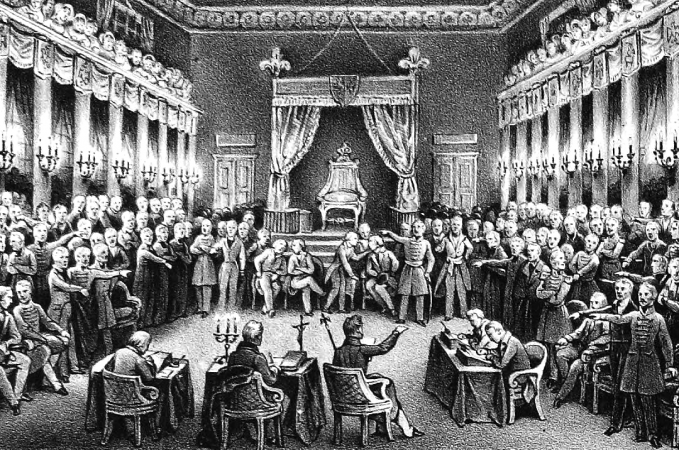

The Chamber of Deputies gathered after the service, which opened the sejm proceedings, attended by the king, the senators and the deputies. Then, led by the oldest deputy (“old staff”, the same voivodship), the deputies chose the new marshal. It was followed with carrying out the rugi. Then, the deputies proceeded to the king in the senate, where the greeting of the deputies took place. The chancellor spoke on the behalf of the king and then the deputies were to kiss the ruler’s hand. In that way the Chamber of Deputies joined with the senate in a joint debate. At first, the royal proposals were announced, presented by the chancellor, the foreign envoys were heard, the Court Treasurer reported his accounts. Then the senators’ wota were presented by every senator. The Chamber of Deputies joined the senate after the wota, what meant that the proper proceedings began. The subjects of the debate were the projects proposed by the king. Own proposals were also presented, as well as claims and complaints. Every deputy had the right to file a petition, presenting them to the marshal, what was referred to as “submitting project to the marshal’s staff” (staff was the symbol of marshal’s office). The king decided if to include the deputy’s project in the proceedings. Similarly, the king had the right to conceal the proceedings if the matter was of great importance. During the debate the Chamber of Deputies maintained contact with the senate through its deputations in order to inform about the course of the proceedings, what was also of consultation advice, heard in the senate by the king, who - after consulting with the senate, had the right to influence the proceedings by answering the deputies. During joint debate of the Chamber of Deputies and the senate the decisions were made and the prepared resolutions were adopted. Adopting a sejm resolution required the common consent, so unanimity. As a result, all the resolutions of a particular sejm were a whole set. Reaching unanimity was extremely difficult and quite often if the sejm could not reach an agreement regarding one resolution, it was often dissolved without adopting even a single one. After the whole proceedings regarding adopting the resolutions, the marshal of the Chamber of the Deputies began the last ceremony, so leave-taking, ended with kissing the monarch’s hand. If the sejm succeeded and adopted resolutions, all the participants went to the church, in which a formal and festive Te Deum Laudams was said.

See: S. Kutrzeba, Sejm Walny dawnej Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej [The General Sejm of the former Commonwealth], Warszawa 1921; J. Bardach, Początki sejmu, [The beginnings of the sejm] in: Historia sejmu polskiego [The history of Polish sejm], t. 1, Warszawa 1984, red. J. Michalski, s. 5-62. W. Uruszczak, Sejm walny w epoce Złotego Wieku [1493-1569] [The general sejm in the Golden Age] in: Społeczeństwo obywatelskie i jego reprezentacja [1493-1993] [Civil society and its representation (1493-1993)], red. J. Bardach, cooperation: W. Rudnik, Warszawa 1995, s. 48-61; W. Uruszczak, Sejm walny koronny w latach 1506-1540 [Crown Great Sejm in 1506 - 1540], Warszawa 1980. W. Uruszczak, Sejm w latach 1506-1540 [Sejm in period 1506-1540], in: Historia sejmu polskiego [The history of Polish sejm], t. 1, Warszawa 1984, red. J. Michalski, s. 63-113. A. Sucheni-Grabowska, Sejm w latach 1540-1587 [Sejm in 1540-1587 ], in: Historia sejmu polskiego [The history of Polish sejm], t. 1, Warszawa 1984, red. J. Michalski, s. 114-216; K. Grzybowski, Teoria reprezentacji w Polsce epoki Odrodzenia [Theory of representation in Renaissance Poland], Warszawa 1959. W. Czapliński, Sejm w latach 1587-1696 [Sejm in period 1587-1696], in: Historia sejmu polskiego [The history of Polish sejm], t. 1, Warszawa 1984, red. J. Michalski, s. 217-299. E. Opaliński, Sejm srebrnego wieku 1587-1652. Między głosowaniem większościowym a liberum veto [Sejm of the Silver Age 1587-1652. Betwixt majority voting and liberum veto] , Warszawa 2001; I. Malec-Lewandowska, Sejm walny koronny Rzeczypospolitej i jego dorobek ustawodawczy [The Crown general sejm of the Commonwealth and its legislative achievements]. 1587-1632, Kraków 2009; H. Olszewski, Sejm Rzeczypospolitej epoki oligarchii (1652-1763). Prawo-praktyka-teoria-programy [Sejm of the Commonwealth in the oligarchy era (1652-1763). Law-practice-theory-programs], Poznań 1966;3, Poznań 1966). S. Ochmann-Staniszewska, Z. Staniszewski, Sejm Rzeczypospolitej za panowania Jana Kazimierza Wazy. Prawo-doktryna-praktyka, [Sejms of the Commonwealth under the rule of John II Casimir Vasa. Law-doctrine-practice] T. 1, Wrocław 2000, s. 276-291. J. Michalski, Sejm w czasach saskich, [Sejm under the rule of Wetting dynasty] in: Historia sejmu polskiego [The history of Polish sejm], t. 1, Warszawa 1984, red. J. Michalski, s. 300-349.